By Richard Devine, Social Worker for Bath and North East Somerset Council

NOTE: If you are receiving this via e-mail it may be cut short by your e-mail programme and/or the graphics may be distorted. You may wish to click the link and view it in full.

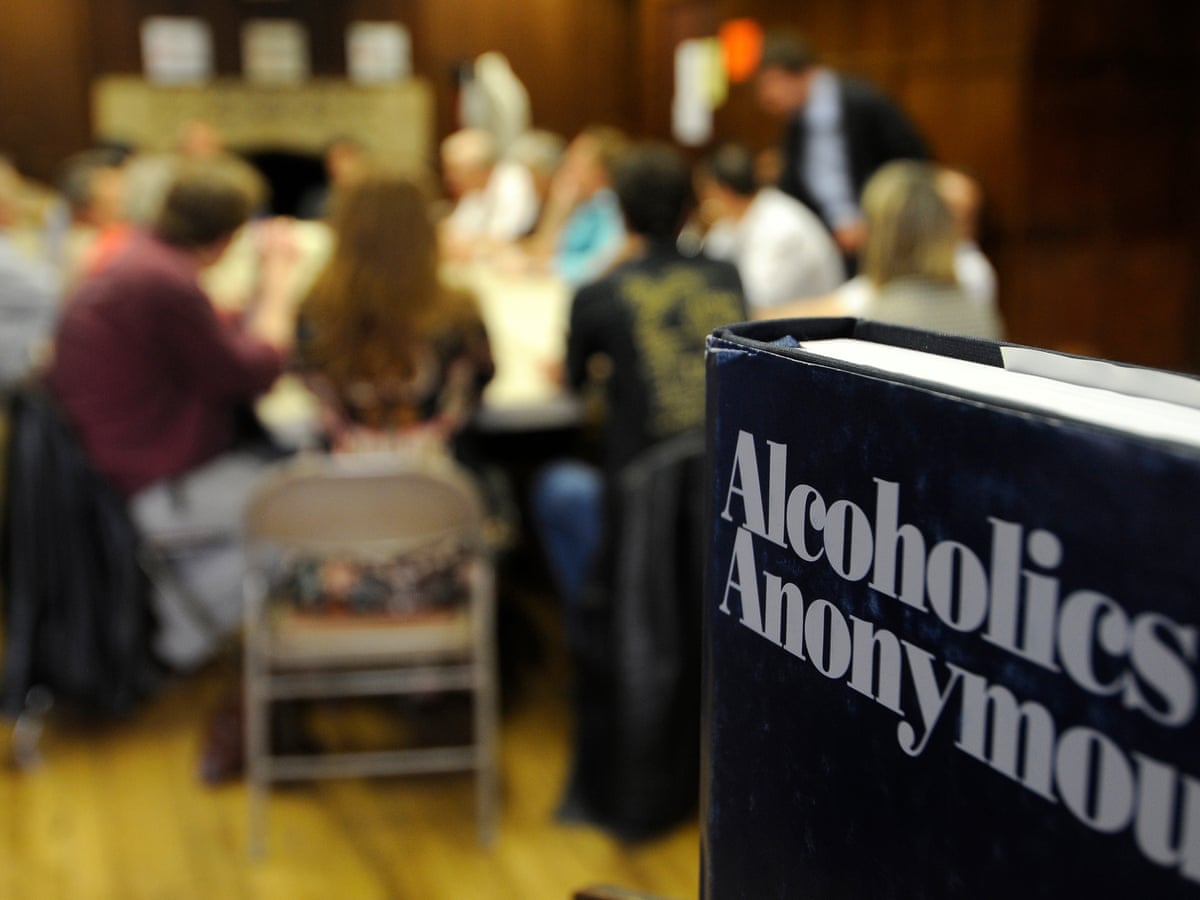

The following is an essay I completed when undertaking a Masters in Attachment Studies at Roehampton University (2016-2018) as part of a Naturalistic Observations Module. One aspect of the module was to observe a group setting and for reasons outlined in the essay my choice for Alcoholic Anonymous will become apparent. It is a couple of years old and I have left it unedited, apart from a few typos that I couldn’t resist correcting. I wanted to share this because Alcoholic Anonymous, in my opinion, is an under-considered and under-utilized resource for parents suffering from addiction. I suspect this is partly because Social Workers or other related practitioners aren’t aware of Alcoholic Anonymous (or related support such as Cocaine Anonymous) or if they are aware of its existence, they are unclear about what it entails and how profoundly beneficial it can be. I hope this blog will shed light on the existence and function of AA so that it can be considered more frequently as an option for parents experiencing addiction alongside the more well-known and utilized drug and alcohol services.

I also think there is a lot we can learn from AA about how to support parents with issues other than addiction. It is a self sufficient system of support, with no governmental or charitable funding that depends primarily on those who have benefited from the programme contributing back by helping those still suffering with alcoholism.

‘Every addiction arises from an unconscious refusal to face and move through pain. Every addiction begins with pain and ends with pain’

(Tolle, 2005; 127)

Introduction;

Alcoholics Anonymous (AA) is a fellowship of men and women who come together to share their stories, courage and hope with the primary purpose of achieving sobriety and helping others achieve sobriety (Alcoholic Anonymous, 2001). AA and my experience of attending three separate meetings will be the focus of this commentary.

I have previously attended such meetings as a result of addiction and alcoholism being a key feature of my own childhood experiences, and to some extent my adulthood. My dad was a chronic alcoholic and a prolific drug user throughout his adult life, albeit with intermittent and short periods of abstinence. He attended multiple rehabilitation centres during my adolescence, all of which were guided by AA and the twelve steps. Furthermore, my elder brother is in recovery after spending nearly a decade misusing drugs and alcohol, also during my adolescence before he achieved sobriety 15 years ago. He continues to attend AA on twice-weekly basis and it is with his assistance that I had the opportunity to attend these meetings. Therefore it is not coincidental that I have chosen to attend these meetings. I suspect that much like my professional occupation, I have chosen to attend AA for two intertwining and inseparable reasons. Firstly, out of interest and intellectual curiosity. Secondly, as a sub-conscious and vicarious endeavour to further understand my own developmental experiences and subsequent psychological functioning.

Irrespective of the possible motivating factors, I endeavored to approach this experience open minded, allowing myself to be immersed into the group setting yet alert and attentive to my internal and external environment. Two key themes arose from my observation. Firstly the underlying reasons for addiction. Secondly the importance of connection, both on a physical and spiritual level. Therefore, these two themes will be the focus of this commentary.

Commentary and Analysis;

The meetings I attended took place in a large church hall. The Church was situated in a row of Victorian houses, almost crammed in the middle, on a road that ran parallel to a main city centre road. Therefore, whilst in the heart of a city, the church was obscurely positioned and unlikely to be noticed unless being specifically searched for. During my three observations, several features remained the same and these included; some people stood outside the church smoking cigarettes chatting pleasantly and drinking tea/coffee out of paper cups as I arrived and walked into the church; the layout of the room; a friendly albeit different recovering addict serving tea and coffee, and the general structure of the meeting. Surprisingly quickly, these different forms of external stimuli became positively associated and imprinted in my mind. Individually and collectively they came together to signify that I was to experience some predictability, stability, and peace for the forthcoming hour or two. I noticed early on into the first observation how relaxed I felt;

Despite the room being full of people whom I did not know, apart from my brother, the environment was warm and welcoming. Somehow, I felt it to be inclusive and non-judgmental and this allowed me to feel at ease; a sense of ‘homeliness’. I felt the wonderful, inexplicable benefit of human connection whilst simultaneously experiencing an absence of socially motivated anxieties that I am usually accustomed to in social situations.

As indicated above, each meeting followed the same structure and involved a host beginning the meeting by providing a brief overview of the aims of AA, followed by a member reading a passage of AA literature. Then, three speakers proceeded to spend fifteen minutes each sharing their journey into addiction, recovery and abstinence. Each of the speakers was different in terms of their age, gender, socio-economic circumstances, provision of education, current professional roles, family make-up, journey into addiction, and age in which sobriety was achieved. However a consistent feature that permeated each of the speaker’s stories was loss and a sense of being disconnected and not ‘fitting in’. These deep-rooted feelings always manifested in their childhood. As detailed by a woman during my second observation;

She wasn’t sure when she became an alcoholic but retrospectively she realized that she was always an alcoholic. She explained that she experienced severe social anxiety and doesn’t like big crowds. She said her parents divorced when she was 5, and there was a lot of rowing and drinking. Every time she felt scared, or fearful but also when she felt happy she drank and would get really drunk resulting in blackouts. She said, ‘inside I was dying’ and ‘I was lonely and was just fixing those emotions’ adding that she was trying to ‘fill that hole in the soul’.

Although the stories differed, they all shared the experience of being necessitated to deal with overwhelming feelings, such as fear, anxiety, fear of rejection, incompleteness, and loneliness. To this effect, alcohol and accompanying substances were often used as a solution to their immediate problem, and in every case, it was successful in the short term. Many of them described the pleasure deriving from experiencing momentary reprieve from their internal state of anxiety, loneliness and inner despair. Felitti (2004; 8) proposes that addiction could be best understood as ‘unconscious although understandable decisions being made to seek chemical relief from the ongoing effects of old trauma’. Paradoxically however, excessive alcohol use exaggerated many of their pre-existing difficulties, and often led to a lifestyle that further reinforced their feelings of not being good enough and ‘not fitting in’. For example, their alcoholism resulted in conflictual relationships, selfish patterns of behavior and difficulty meeting their basic care needs with sustained employment rarely existing in their lives. As pointed out by one speaker realised after she was addicted, ‘drinking didn’t solve any of my problems, it made problems worse and created problems that wouldn’t otherwise have existed’. These individuals persevered with a self-protective coping mechanism that deceived them into believing it could remedy their difficulties. Sadly, however, they often did not realize the extent of their alcoholism until long after it had become an embedded, highly addictive, and destructive force in their lives.

It became apparent that an understanding of alcoholism cannot be understood in the absence of an exploration of aetiological factors that contribute to the development of addiction, namely loss and a deep sense of psychological loneliness often consequential of an emotionally disturbed childhood. As pointed out by Mate (2008: 34):

‘The question is never “Why the addiction?” but “Why the pain?”’

Mate suggests that addiction is an individual’s attempt to soothe emotional pain in the absence of healthier coping mechanisms, such as relationships and thus ‘addiction is always a poor substitute for love’ (Mate, 2008: 249). Given the reported similarities in the biology and neurology involved in addiction and love (Panksepp, et al 1978; Insel, 2003 cited Cozolino, 2014: 116) it seems reasonable to postulate that an emotionally deprived and/or relationally challenging childhood substantially increases the likelihood of the developing child seeking to address this through alternative, albeit unhealthier and less fulfilling means.

It follows therefore that any attempt at addressing addiction, an adaptive response to dealing with difficult emotions without relational support would invariably need a process that involves addressing difficult emotions with significant social support. During the first meeting, a man described attending a private school before his parents separated resulting in him moving to a mainstream primary school. He described how the separation of his parents and change in school was the catalyst for his emotional difficulties which he carried through into his adolescence and adulthood. He began drinking in adolescence and immediately felt reassured as it lessened his anxiety and loneliness. As the years went on his drinking become progressively worse resulting in a series of failed relationships, as well as the loss of his house and several jobs. His drinking developed to the extent that he could no longer leave the house to buy alcohol without first drinking alcohol. He would consume alcohol until he passed out and would hope that he would never wake again. He depicts how he made the change;

Eventually, after many years, when he was nearly 40 he sought help through AA which he knew about from a family member. He attended a group and this marked the beginning of his journey to sobriety. He described attending his first meeting and felt the acceptance and hope: when he heard people speak it resonated with him. He said he got involved and this provided him a place where he didn’t feel an outsider. He ended by saying that he didn’t think he would be here without the love, support and encouragement from AA.

His reported experience of attending his first AA meeting and experiencing a sense of acceptance was a feeling he shared with all the speakers whom I observed and a feeling that I also experienced despite not having an alcohol addiction. It would seem that this feeling of belonging, acceptance, and connection is the foundation on which the addicted individual can begin to work a program (12 steps). The twelve-step program involves admitting powerlessness over alcohol, believing in a power greater than themselves, undertaking a fearless moral inventory and making amends and helping other individuals to achieve sobriety (Alcoholic Anonymous, 2001). As far as I can tell, AA offers individuals who have experienced shame, guilt, fear and anxiety resulting from their developmental experiences compounded by their alcoholism an environment in which they experience belonging, connectedness, and emotional safety. As identified by Crittenden (2016: 316) ‘other people can fulfil the attachment functions of offering safety’…and ‘comfort’ when this has not been provided by the family.

After realizing that AA offered an environment that provided a sense of belonging, the next common theme that was discussed by many of the speakers was their relationship with ‘higher power’. It was clear that this was a fundamental aspect of their recovery, but their interpretation of the meaning of ‘higher power’ varied from person to person aside from the fact they all believed in a power greater than themselves. The final speaker, during my final observation, explained his interpretation of higher power;

‘Higher power expresses itself through people, through the love in the fellowship, through the love of people, through people being together and helping each other, and it is also something that is present in my mind that is not part of my ego, a part of my mind that is related to other people’

I thought this to be a simple, yet beautiful and eloquent description of ‘higher power’, and it resonated with my deeply felt experiences of attending the meetings. The expectation that the recovering addict will develop a relationship with a higher power or God was an integral aspect of their journey into sobriety. If ‘healing occurs in relationships’ (Crittenden, 2008; 316) can a relationship with a deity, with no tangible form fulfil the same function as a relationship with another person(s)? Granqvist and Kirkpatrick (2004; 227) have argued that god functions psychologically in the same way a healthy attachment figure does, and go so far as saying that a ‘relationship with God would function as a surrogate attachment relationship, assisting the individual in regulating states of distress, and thereby promoting felt security’.

The combination of a strong, stable, and un-wavering collective group of people willing to unconditionally accept the individual alongside the development of a relationship with a ‘higher power’ seems to offer a powerful antidote to the pervasive feelings of loneliness, anxiety and despair that led them into and sustained their addiction to alcohol. It is in this context that individuals can subsequently work through the other steps in the program which involve addressing their psychological vulnerabilities. Once they have achieved sobriety and recovery then finally they seek to support others who wish to achieve sobriety. Having benefitted from relationships providing love, care and system for change they can now seek to provide love, care and support to others; no doubt an incredibly emotionally and spiritually nourishing position experience.

Conclusion;

In undertaking this observation I have learned about the value of social support, community, and relational cohesion in achieving and maintaining emotional and mental wellbeing, particularly in the context of challenging life experiences. Although I don’t agree with the statement in its entirety, I have come to appreciate what Johann Hari (2017) means when he says ‘the opposite of addiction is not sobriety. It is human connection’. As identified by Panksepp et al (2002) individuals can use social relationships to support the brain systems that have been treated with addiction.

As well as my learning from this assignment as described above I cannot deny the benefit to my psychological wellbeing attending these meetings. The experience of witnessing another individual share their deepest worries, anxieties and fear in the context of a supportive environment was grounding and humbling. As a result of my own developmental experiences I too have developed self-protective strategies, namely the inhibition of affect. This has been accompanied by a pervasive sense of inadequacy and worthlessness that results from having your emotions unintentionally yet persistently ignored or devalued by your carers. Furthermore, I also found reprieve, and escape from the inner deep rooted unhappiness of myself through drugs and alcohol during my adolescence and early adulthood. I was fortunate enough to have enough support from my family and friends, and a fulfilling job to see the limitations of this self-protective coping strategy, and thus have my emotional and spiritual needs met through alternative healthier pursuits. Nevertheless, I have since worked excessively throughout my adulthood in a more socially acceptable and at times rewarding means of managing my insecurities, feelings of inadequacy and desire to avoid being too emotionally engaged with important people in my life. Undoubtedly this has had an addictive component given my apparent unwillingness to address this for many years (until recently), despite the obvious negative implications for my physical, psychological and relational health.

Attending the meetings provided psychological space to reflect on this, and hearing the stories of other individuals gave me two things. The first being perspective. I was able to appreciate that negative emotions are experienced universally, albeit on a spectrum of severity often tied to developmental experiences. Negative emotions do not discriminate based on age, gender, socio-economic background nor professional success and in this respect they are impersonal. It is abundantly clear that alleviating difficult and uncomfortable emotions will not occur through external stimuli (alcohol, drugs, work) but through connection with a higher power, however you wish to define that, as well as meaningful and reciprocal connection with others and acceptance and honesty. Secondly, I experienced a profound hope that positively infused my mood for hours, if not days after attending the meetings. The honest accounts of individuals’ journey from utter despair and anguish to connection with others at AA and ultimately their recovery offers great hope regarding a human’s ability to change, grow and adapt to a healthier way of coping despite the most adverse beginnings in life. To this effect, I agree unequivocally that,

‘Hope is contagious’

(Crittenden, 2016; 316).

By Richard Devine (16.04.21)

If you have found this interesting/useful, you may wish to consider scrolling down further, and join a growing community of 210+ others in signing up for free blogs to be sent directly to your inbox (no advertisements/requests/selling). I intend to write every fortnight about matters related to child protection, children and families, attachment, and trauma. Or you can read previous blogs here

Bibliography;

Alcoholics Anonymous. (2001). Alcoholics Anonymous, 4th Edition. New York: A.A. World Services.

Cozolino, L (2014). The Neuroscience of Human Relationships (2nd ed). W.W.Norton & Company. London.

Crittenden, P.M. (2016) Raising Parents: Attachment, Representation and Treatment,(2nd ed.) Abingdon, Oxon: Routledge

Granqvist, P. and Kirkpatrick, L. A. 2004. Religious conversion and perceived childhood attachment: A meta-analysis. The International Journal for the Psychology of Religion, 14: 223–250.

Granqvist, P. and Kirkpatrick, L. A. 2008. “Attachment and religious representations and behavior.”. In Handbook of attachment: Theory, research, and clinical applications, , 2nd ed. Edited by: Cassidy, J. and Shaver, P. R. 906–933. New York, NY: Guilford.

Hari, J (April, 2017). Johann Hari: ‘The opposite of addiction isn’t sobriety – it’s connection. The Guardian. Accessed from https://www.theguardian.com/books/2016/apr/12/johann-hari-chasing-the-scream-war-on-drugs (accessed on 15.06.2016)

Maté, G. (2008). In the Realm of Hungry Ghosts: Close encounters with addiction. Toronto: Knopf Canada.

Mate, G (2012) Addiction: Childhood Trauma, Stress and the Biology of Addiction. Journal of Restorative Medicine, Volume 1, Number 1, 1 September 2012, pp. 56-63(8)

Panksepp, J., Knutson, B., & Burgdorf, J. (2002) The role of brain emotional systems in addictions: a neuro-evolutionary perspective and new ‘self-report’ animal model. Society for the Study of Addiction to Alcohol and Other Drugs, Addiction, 97, 459–469

Tolle, E (2005). The Power of Now. Hodder and Stoughton. London.

Vincent J. Felitti, MD. (2004). Origins of Addiction: Evidence from the Adverse Childhood Experiences Study

Hi Richard,

This blog on attending AA just confirmed how important connection is to humans- it is basically our life âessence or the essence of lifeâ I can certainly see how the group environment can nurture its members in a very powerful way.

And have experienced it myself as a member of a parenting group and then becoming involved in facilitating those groups.

And I suppose groups that provide this are in a way pseudo family set ups, as you say.

Thanks for that.

Ruby

LikeLike

Great post! I hope you got an “A” on this paper 🙂

LikeLike

Great blog, I’ve worked in and around the field of substance misuse for over three decades and I think this is the best interpretation of a higher power I’ve come across….

Higher power expresses itself through people, through the love in the fellowship, through the love of people, through people being together and helping each other, and it is also something that is present in my mind that is not part of my ego, a part of my mind that is related to other people’

Thanks for sharing your observations, I found them them deeply insightful!

LikeLike