By Richard Devine, Social Worker for Bath and North East Somerset Council (26.03.21)

NOTE: If you are receiving this via e-mail it may be cut short by your e-mail programme and/or the graphics may be distorted. You may wish to click on the link and view it full.

Introduction:

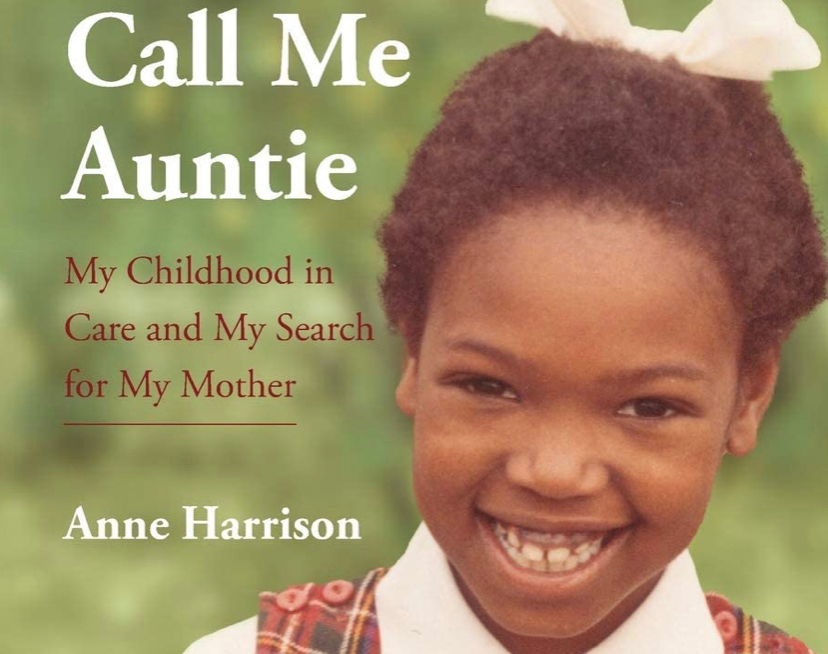

I recently read a book recommended by a colleague, Becky Wills called ‘Call me Auntie: My Childhood in Care and Search and My Mother’. I found this book a captivating story and revealing insight into the life of Anne, a young black girl placed into foster care and then moved to residential care in the 1960’s and 1970’s. Her resilience in the face of unimaginable adversity, and her journey from foster care to residential care to becoming Warwickshire’s first black police cadet, a police officer, a social worker and more recently a magistrate is nothing short of astonishing.

A striking feature of the book was the degree to which many of the themes in the book bear relevance for today.

After I read the book, I was so moved and remained curious about Anne’s story that I wanted the opportunity to speak with her. To my pleasant surprise, she very kindly and generously agreed. Below is the video of the discussion that we had together:

As a result of reading Anne’s brilliant book, as well as having the privilege of being able to speak with her, I will expand on three themes that I think have relevance for current social work practice

- Appearance is not always reality

Throughout the book, a theme that Anne describes is her temperament. She noted how the records described her as content, quiet and although she would occasionally experience ‘fits of short temper’ these passed quickly. After Anne had spent several years with foster carers they decided to emigrate to Australia, and she was placed into residential care. Her Social Worker recorded the separation:

‘Anne left her foster home to-day quite calmly although I noticed that her eyes filled with tears when Mrs Reed said “Good-bye.” She is a very quiet controlled child and one cannot judge how upset she is by outward appearance.’

Anne, in her book, expanded on this theme, detailing how she became ‘somewhat detached from what was going on around me’. She wrote, ‘It’s hard for me to find words for what I felt at that time or to describe the depth of my confusion and depression. If I struggle to find the words now, I certainly had none when I was nine’. Later in the book, she would describe how ‘Behind my self-control, there was a good deal of anxiety and unhappiness’.

Anne’s presentation as self-contained, self-sufficient, and seemingly unaffected by the abandonment of her mother (and father) and loss of her fosters carers (primary attachment figures) belied and concealed to others the underlying distress and torment associated with these experiences. In my experience, Anne’s account, whilst undoubtedly unique to her reflects a pattern of coping that I have observed frequently with children subject to adverse experiences and/or placed into alternative care.

As a result of having their emotional needs ignored and/or rejected intentionally and/or unintentionally, children, like Anne learn to dampen down their dependency needs. Instead of expecting adults to be available to comfort and protect them, they minimize and deny their feelings, and instead try and meet the needs of adults, or develop a compulsively compliant strategy and/or detach from relationships altogether and attempt a ‘do it by yourself’ self-reliant strategy (Crittenden, 2016). These strategies are borne out of self-protective necessity and are in fact, a strength of a child’s ability to adapt and psychologically protect themselves from the painful and often overwhelming feelings associated with rejection and loss, such as worthlessness and shame. However, as Anne discussed in our interview, there can a cost to the adoption of these strategies. Not least, a child’s underlying distress can easily be overlooked. Indeed, some well-intentioned carers and professionals may unintentionally reinforce the strategy by praising a child’s self-containment, performance, and independence. Also, there may be long-term costs. For Anne, she described difficulty in forming emotionally close relationships in adulthood. The strategy she developed helped her in the short term (i.e. adaptive) but it created some challenges in adulthood, even though the context that necessitated the development of the strategy changed (i.e. maladaptive).

A risk of being compelled to detach and inhibit negative emotion is that it becomes deeply embedded, implicit, and carried forward into adulthood without awareness (Crittenden, 2016). For some children and young people this may result in long-term problems with trusting others, expressing emotions and self-reliance (avoiding close relationships due to feelings of unworthiness and experiencing all relationships as disappointing). In turn, this can lend itself to an increased likelihood of drug misuse (to help suppress negative feelings), depression (chronic inhibition of negative feelings alongside feelings of worthlessness), sexual promiscuity (seeking sexual/physical closeness whilst maintaining emotional distance) and/or abusive relationships (relationships function best with denial of own feelings and overly focusing on needs of others).

It is important therefore that we acknowledge that children, especially children who have been separated from their parents will need to develop strategies to cope. Some of these strategies may conceal, as Anne described in her case, a ‘depth of confusion’ and ‘depression’. It is a remarkable feat of ingenuity that children develop these strategies, however, we should also gently and tentatively explore beneath the self-protective veneer to help children process the feelings associated with the loss and rejection. A failure to do so runs the risk of children’s profound distress being unacknowledged and thus reinforcing their belief that their feelings, and by default them as people, do not matter.

- Labels (Being ‘black’ and in ‘care’)

Anne described in her book and in our interview how she was defined in her childhood by two labels. In her book she wrote:

I carried two labels. I was black, and I was also a child in care. My life in the Charles Street home [the residential home] was painful, and both labels contributed to my sadness and discomfort. Meanwhile I was in denial, both about being black and about the fact that I was not a birth member of the Reed family [her foster carers]. None of my carers ever did anything to lift those burdens and probably nobody had a clue how to address this.

Further on, she also wrote:

I am still amazed that none of my carers thought to help me with my identity. Perhaps it was understandable that the home staff did not know about black skin or hair care, let alone black culture. Less understandable is that none of them made any effort to find out.

I have emphasized the last sentence because the past year has been important for increasing our cultural awareness and raising expectations in how individuals from different ethnic backgrounds in our country are represented and treated. I fear, based in part on my own ignorance and blind privilege that insufficient attention is given, still, to the role of race and ethnicity in social work, especially for children in care. Reading Anne’s book was, for me, another reminder to make effort to speak to young people and their families about their race/ethnicity and consider what can be done to support them to embrace and celebrate their identity.

- The lifelong impact of loss and the search for parental acceptance

A central theme of Anne’s book was her quest to find her mother and understand the reasons why she was unable to care for her as well as understand her heritage and father. Sadly, what she experienced was an agonizing, multi-decade-long journey of sparse, limited, confusing messages from her mother who ultimately couldn’t provide her what she sought (or needed and deserved).

There are two sections of the book that reveal the effects of the loss of her mother at different stages in her life. Anne’s mum left her when she was 7 months old and she remained untraceable until Anne was 13 years old. Contact was established between the authorities and her mother, so Anne was told about this and attempts were subsequently made to facilitate a relationship. At the same time, she learned for the first time that she had a younger brother who was also placed into care by their mother. She wrote:

‘Suddenly I was free to dream. In my head I had always held a vision of my mother, what she was like, and how she would be with me. Every birthday and Christmas…I imagined that she would come and get me or that I would receive a card and a present. Although this had never happened…

Now I had a brother to dream about too. The thought that I had a brother was amazing. I felt the same for him as I did for my mother. In fact, they were more than just a mother and a brother – they were my family! …. I was confused, overwhelmed, and utterly wowed’.

In my experience, children in care often fantasize about their parents, even when the level of harm or abandonment by their parents necessitated them to be cared for by alternative carers. Separation often constitutes psychological trauma* – a deep, primordial, and often irresolvable despair associated with the loss of the biological parent can often scar children for life. With exceptional alternative care the scar can be healed but it never disappears. Many children don’t receive exceptional care however and so the scar often remains open and visible. I am not sure enough consideration is given to this. Some children learn to cope with the desperate yearning by disconnecting themselves from the feelings because it’s emotionally intolerable, whereas some children can be extremely angry with their parents, which is a way of communicating their distress that is more emotionally tolerable than acknowledging their sadness and vulnerable need for parental attention, affection, and acceptance. For these reasons, it can be hard to appreciate how children who have been separated from their parents truly think and feel.

Unfortunately for Anne, her mother was not able to commit to a relationship with her nor provide her with the answers she needed. What is notable however is that she remained desperate to have a relationship with her, or at the very least, acquire some knowledge about her, her history and family throughout her adult life.

Four decades later and multiple failed attempts to establish a relationship with her mother, Annie described how she was left feeling:

‘…there really was a void in my life, one that I looked to her to fill. The void was emotional: all my life I had needed a mother and after nearly 40 years I still hoped for something of a mother- daughter relationship. But the void was not only emotional: I also wanted knowledge. I wanted to learn about my heritage, my father, my grandparents, and my wider family. I wanted to know about my ethnicity…

Even now, a week does not go by without me thinking about her. I think about what might have been and what she’s missed. She was meant to be part of my family, and it never happened’.

This speaks powerfully to the lasting effects of ruptured parent-child relationships. In my role, I rarely think about the child I am working with as an adult. What are the effects of that on my practice? Do I over-estimate the importance of short-term safety and wellbeing of the child? We can protect children from the immediate present harmful aspect of care by placing them in alternative care, but what does that protection look and feel like when that young person is 20? Or 30? Or 60 years old? And what happens once children are removed due to legitimate concerns for their safety – how much do we do to preserve, maintain or even repair those biological relationships? To maximise what the parent can contribute to their child’s life, even when it remains unsafe for them to return home. Do we organize our services and support on the basis that many children leave care and return home once they’re old enough? What do we do to help and strengthen the parent’s capacity to be available for their children during the months and years they are in alternative care?

On a final note, Anne did manage to connect with her brother. This process, as she detailed in her book was not straightforward nor easy because they had not grown up together. She wrote, ‘At first, John and I did not know how to act as brother and sister. We had no shared memories’. Nevertheless, they remained close.

‘Today my funny, intelligent, kind brother is among the people closest to my heart and soul’.

Her brother, whom she did not know for 13 years is among the people ‘closest’ to her ‘heart and soul’. An evocative illustration of the importance of family. When children have disrupted relationships with their parents, then brothers, sisters, aunts, uncles, and grandparents can take in inordinate importance. I am uplifted and delighted to hear of the closeness between Anne and her brother and feel ethically and morally compelled to recognize the power and strength of sibling relations in my practice, especially for children in care.

Conclusion:

I wrote this blog because I wanted to bring attention to Anne’s story. More than anything I would like others to take the opportunity and time to purchase her book and read her story (Found here). We are privileged that children who have grown up in care, such as Anne write and share their stories revealing their personal, intimate, and often painful experiences. If we are involved in this system, in any shape or form, then I believe we have a duty to listen to their stories and more importantly, learn and improve our practice as a result.

*I am using the term 'psychological trauma' in a specific way. That is, ‘failing to understand what happened’ and ‘being unable to regulate strong, motivating feelings that are elicited by associated stimuli in the present’ (Crittenden, 2016: 44).

By Richard Devine, Social Worker for Bath and North East Somerset Council (26.03.21)

If you have found this interesting or useful, you may wish to consider scrolling down further, and join a growing community of 210+ others in signing up for free blogs to be sent directly to your inbox (no advertisements/requests/selling). I intend to write every fortnight about matters related to child protection, children and families, attachment, and trauma. Or you can read previous blogs here

If you have already signed up, then I want to say a huge thank you to you…yes, you! It means a great deal to me that you have joined this growing community to learn and explore the fascinating world of social work.