By Richard Devine, Social Worker for Bath and North East Somerset (05.02.2021).

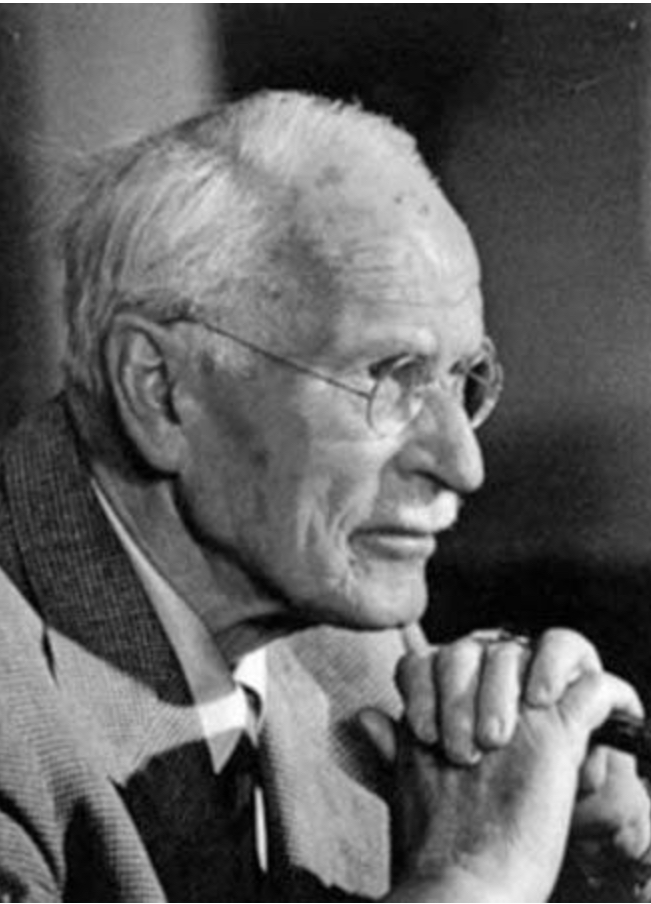

Modern Man in Search of a Soul (1933) is apparently a great introduction to Carl Jung’s theories of analytical psychology. The book is broken down into eleven essays dealing with topics of dream analysis, Freudian psychology, spirituality, religion, and the unconscious. I don’t claim to have understood it all, but that which I did understand, I found captivating. I have pulled out some quotes that stood out for me, and for each one, I will share some thoughts about it.

I have shared 5 lessons in Part 1. In this blog I will share 5 more lessons.

6. Are we any different, truly?

‘If he examines himself he will discover some inferior side which brings him dangerously near to his patient and perhaps even blights his authority. How will he handle this tormenting discovery?’

‘And yet it is almost a relief for us to come upon so much evil in the depths of our own minds. We are able to believe, at least, that we have discovered the root of the evil in mankind. Even though we are shocked and disillusioned at first, we yet feel, because these things are manifestations of our own minds, that we hold them more or less in our own hands and can therefore correct or at least effectively suppress them. We like to assume that, if we succeeded in this, we should have rooted out some fraction of the evil in the world’

Jung, 1933: 53 and 209

Any observable difference in personality or psychological functioning is quantitative rather than qualitative (Plomin, 2018). In other words, we all have the capacity for violence, addiction, mental ill-health, in the same way, we all have the capacity for love, connection, joy – our genes, environment, and culture shape and define which human capacities are expressed, as well as the intensity to which they find expression. No matter how destructive or harmful a parents behaviour might be, I can always see without much effort that I would think and act exactly as they did if I had their family background and experiences. On occasion, I do think and act as they do even with my advantageous life circumstances.

7. The first and second halve of life; the rising and setting of the sun

‘It seems to me that the elements of the psyche undergo in the course of life a very marked change so much – so, that we may distinguish between a psychology of the morning of life and a psychology of its afternoon. As a rule, the life of a young person is characterized by a general unfolding and a striving toward concrete ends; his neurosis, if he develops one, can be traced to his hesitation or his shrinking back from this necessity. But the life of an older person is marked by a contraction of forces, by the affirmation of what has been achieved, and the curtailment of further growth’

‘In the morning it arises from the nocturnal sea of unconsciousness and looks upon the wide, bright world which lies before it in an expanse that steadily widens the higher it climbs in the firmament. In this extension of its field of action caused by its own rising, the sun will discover its significance; it will see the attainment of the greatest possible height, the widest possible dissemination of its blessings–as its goal. In this conviction the sun pursues its unforeseen course to the zenith; unforeseen, because its career is unique and individual, and its culminating point could not be calculated in advance. At the stroke of noon the descent begins. And the descent means the reversal of all the ideals and values that were cherished in the morning. The sun falls into contradiction with itself. It is as though it should draw in its rays, instead of emitting them. Light and warmth decline and are at last extinguished’

Jung, 1993: 59 and 109

Even at 33, I have noticed a shift in my perspective and priorities. I was blindly desperate in my 20’s to achieve some recognition, validation, and security and sought this primarily through work. The perspective and views of others was inordinately important to me. I would bend and stretch myself to elicit and maintain approval. Of course, craving and striving towards others’ approval is not necessarily bad, not least because it facilitates relationships and supports learning and growth. But, I have found tremendous relief by realising that others care a lot less than I had hitherto appreciated. This isn’t to say that relationships and other people’s perspectives do not matter, rather I have learned that I am not being judged anywhere near intensely and harshly as I had presupposed. It is not uncommon to hear from older friends, family members, and colleagues that one pleasure in getting older is the sense of freedom and liberation that can be derived from not being too caught up in other people’s judgement. Perhaps this reflects one of the many psychological changes that occurs when we transition through middle life.

I often think about how I can live my life in a way that my older self will be grateful for whilst not allowing this imaginary time-traveled retrospective thinking to distract from the present moment. According to Jung, I am in the stage of ascending, attempting to ‘discover’ my ‘significance’ and therefore, I should endeavour during this period to realise my potentials with as much force as I can reckon. However, such a venture should be mediated by a recognition that achievement, usefulness, and other such ideals perhaps won’t serve me as well in the latter half of my life as I am inclined to currently believe. Grappling with these ideas is perhaps what Jung would refer to as the ‘art of life’: ‘the most distinguished and rarest of arts’ (1933: 113)

8. Do we have ideas, or do ideas have us?

‘It is true that widely accepted ideas are never the personal property of their so-called author; on the contrary, he is the bond-servant of his ideas….We do not create them; they create us’

Jung, 1993: 118

There are two ways to think about this. Firstly, we can have an idea about ourselves, which is often developed in childhood in response to an event or certain experiences. At some point, we make a decision about who we are, and sometimes this is conscious, but most of the time it is unconscious. This idea about ourselves often generates behaviours and creates relationships in a way that validates the ‘truth’ of the idea, and thus functions as a positive self-reinforcing feedback loop.

Bandler and Grinder, in their book The Structure of Magic (1975: 15) explain how someone may develop the idea or a rule such as ‘don’t express feelings’. They proceed to explain ‘this rule in the context of a prisoner-of-war camp may have a high survival value and will allow the person to avoid placing himself in a position of being punished. However, that person, using this same rule in a marriage, limits his potential for intimacy by excluding expressions which are useful in that relationship. This may lead him to have feelings of loneliness and disconnectedness – here the person feels that he has no choice, since the possibility of expressing feelings is not available within his model’.

It is worth noting that you don’t need to be a prisoner of war to learn that rule.

Attachment theory has demonstrated that a parent unable to tolerate or be available to deal with a child’s negative feelings may lead to the development of that rule (Crittenden, 2016). For example, if a child has a depressed mother then the child may learn that her mother isn’t available when she expresses her needs. In fact, expressing needs/emotions may cause the mother to retreat further. To deal with the feelings of rejection this invokes, the child learns to dampen down her dependancy needs and ignore, suppress any emotions so that she doesn’t need to approach the mother. Diminishing needs and feelings reduces the frequency in which the child’s overtures are rejected. Perhaps the mother can tolerate the child when she doesn’t place any demand upon her and/or express emotion and this may improve the relationship. The child then might learn that relationships function best when she minimises and suppresses her own feelings and places the needs and feelings of intimate others above her own. When this is carried forward into adulthood, the person might unconsciously select a partner who requires them to prioritise their needs, thus reinforcing the need for the rule, ‘don’t express feelings’.

The second way to think about this is in terms of social, psychological, or political ideas. For example, I am fascinated by attachment theory. If someone criticised attachment theory I might easily mistake that as a criticism of me. But attachment theory has nothing to do with me. Apart from it being a piece of knowledge that I happened by chance to stumble into – why would I want to claim to own that? Or allow that to own me?

In the same way, if I was to disagree with someone about a political viewpoint – I do not own that political viewpoint any more or less than the other person own theirs. It just so happens that in our respective positions, with the knowledge we have gathered, that is how the world seems to us. As pointed out by physicist, David Bohm in his book Dialogue (1996), understanding how we form ideas, or how ideas get implanted within us, is just as important as the ideas in of themselves.

9. Humility

‘Indeed, I do not forget that my voice is but one voice, my experience a mere drop in the sea, my knowledge no greater than the visual field in a microscope, my mind’s eye a mirror that reflects a small corner of the world, and my ideas- a subjective confession’

Jung, 1993: 225

One can never be reminded enough of how little we know. Often, what we do know is distorted by our own biases.

10. Grappling with complexity

‘It is in applied psychology, if anywhere, that today we should be modest and grant validity to a number of apparently contradictory opinions; for we are still far from having anything like thorough knowledge of the human psyche, that most challenging field of scientific enquiry. For the present we have merely more or less plausible opinions that defy reconciliation’

Jung 1933: 58

Perhaps more than other fields, caution, humility, and critical rigour should be applied to psychological ideas and theories, for psychology as a scientific field of enquiry is in its infancy. Indeed, many famous psychological experiments, such as ‘ego-depletion’ and the ‘marshmallow test’ have been disproven in what has been referred to as the ‘replication crisis’.

My own, and probably deeply unsatisfactory way to contend with ‘apparently contradictory opinions’ is to use knowledge, ideas, and theories that improve my practice as a social worker. That is the test I apply. Can I use this idea or theory (or a part of a theory) to be a better social worker? As pointed out by Jung ‘one can get along for quite a time with an inadequate theory, but not with inadequate therapeutic methods’ (Jung 1993: 58).

Bonus idea: Dreams

‘Dreams may give expression to ineluctable truths, to philosophical pronouncements, illusions, wild fantasies, memories, plans, anticipations, irrational experiences, even telepathic visions, and heaven knows what besides. One thing we ought never to forget: almost the half of our lives is passed in a more or less unconscious state. The dream is specifically the utterance of the unconscious. We may call consciousness the daylight realm of the human psyche, and contrast it with the nocturnal realm of unconscious psychic activity which we apprehend as dreamlike fantasy. It is certain that consciousness consists not only of wishes and fears, but of vastly more than these, and it is highly probable that the unconscious psyche contains a wealth of contents and living forms equal to or even greater than does consciousness, which is characterized by concentration, limitation and exclusion’.

Jung, 1993: 11

If you really want to understand your unconscious, then paying attention to your dreams is one of the most effective ways to do that. As I was reading this book I became a lot more aware of my dreams. This awareness meant that I was paying attention to the contents of my dreams and I became better at being able to remember them. However, in my experience dreams can be too direct of a window into the unconscious and can be frightening and disturbing. There is a good reason most of us don’t remember them (and it is not because we are aren’t able to!).

By Richard Devine (05.02.21)

If you have found this interesting/useful, you may wish to consider scrolling down further, and join a growing community of 200+ others in signing up for free blogs to be sent directly to your inbox (no advertisements/requests/selling). I intend to write every fortnight about matters related to child protection, children and families, attachment, and trauma. Or you can read previous blogs here