By Lys Eden (14.08.20)

Preface by Richard Devine: This is a guest blog by Lys Clark, care experienced social work student. I found this to be a thoroughly captivating and thought provoking piece, in which the concept of resilience is explored. Lys lucidly and incisively articulates concern with the term. She persuasively argues that it is often used to absolve us of our responsibilities and/or conceals and thus minimises the effects of traumatic experiences upon children (sometimes with devastating consequences). Lys speaks from an authoratative position on this subject, drawing upon her own experiences but also as a social work student. I think this blog sheds clarity and insight, but importantly challenges us to think afresh about the use of the term.

Introduction:

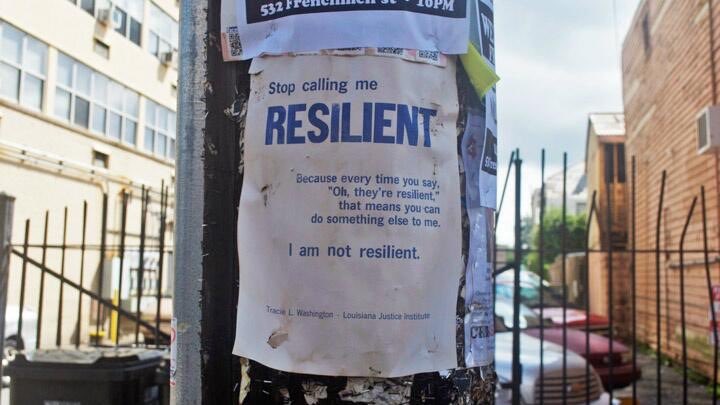

I have grown disillusioned with the word ‘resilient’. Whether it is used to reinforce individualistic ideals; a disparaging remark loaded with judgment and blame – ‘you need to be more resilient’ – or as a misguided attempt to adopt a strengths-based approach – ‘wow, they are so resilient!’, there is something in the way it is individualised and then commodified that bothers me.

So I ask…what is so attractive about resilience? Perhaps the appeal is that the concept has become an empty vessel which organisations can fill in order to sustain neoliberal agendas. This is evident in our conceptualisation of resilience within children and families social work, often concealed as ‘protective factors’ under the pretense of strength-based approaches, perhaps as a way to manage the increasingly high thresholds for statutory intervention. Don’t get me wrong, strengths-based practice has its place but equally, it needs to be carefully balanced against the risk factors. All too often, resilience is misused to absolve our responsibilities to keep children safe – if we do not acknowledge the risks, then we can pretend that they are not there.

As somebody who retains a dual identity – in which I am both a student social worker and a care experienced adult, not only do I see this occurring in practice but also reflected in my own experiences. My perceived resiliency became a chronic justification to slap ‘NFA’ on countless social care referrals throughout my childhood. I will never forget the sentiments uttered by one of my social worker’s, “You’re 15 now, you’ve only got a year until you can go into a hostel”. Still now, I find this hard to come to terms with; the recognition of how dire my situation was, but an unwillingness to do anything about this under the guise of ‘resilience’ as well as a presumption that I would be able to cope living independently at such a young age.

The devastating consequences of ‘resilience’:

I recently read a heart wrenching serious case review (SCR) that echoed many of my own experiences, and demonstrated the devastating consequences of the concept of resiliency. This is far more than semantics. Sasha was consistently described as ‘resilient, highly articulate, engaging, friendly and mature for her age’. She had endured countless adversities throughout her childhood – made evident by the revolving door of child protection procedures and care proceedings. Despite this, she returned to her mother’s care in 2009, and was described as taking on a caring role for her mother, unidentified as such at the time. Sadly, her mother’s health deteriorated frequently throughout the years, leading to Sasha living with her older half-sister for a while after it was ‘assessed that Sasha was resilient and that no additional action was required’. She returned to her mother who unfortunately became ill again. As a result of Sasha’s erratic involvement with mental health services and youth offending, coupled with risks surrounding exploitation, children’s services decided to accommodate her in care and placed her in a small unit to prepare her for independence when Sasha was 17. However, once in the care of the local authority, risks continued to be masqueraded by her ‘resilient’ nature. Here is a poignant excerpt from the SCR:

There is no doubt in my mind that Sasha carried immense courage, determination, and strength. She also carried wounds no child should ever have to hold. I use the term ‘child’ intentionally as we tend to alter our perceptions of ‘vulnerability’ and risk when we think about adolescents, as if age is synonymous with a greater capacity to cope with trauma. The bright, articulate, ‘beyond their years’, resilient child is often one who has carefully constructed these behaviours as a way of maintaining safety by supporting their caregivers needs, eliciting some form of engagement from an otherwise unavailable caregiver.

As pointed out by Beacon house, Pat Crittenden says ‘there is no such thing as disorganised attachments – children always organise their behaviour around danger.’ Crittenden (2016) also identifies that some children can utilize a compulsive caregiving strategy and have a tendency to display ‘false positive affect’ which on the surface can appear congruent but is often a result of having to suppress their own needs and feelings in order to prioritise their caregivers. In essence, they are taught not to show negative affect – to not show their needs, their vulnerability, and their wounds. Although we may see glimpses of their pain oozing from the cracks of their shattered self they have hurriedly assembled together, this is often fleeting and perhaps only serves to reinforce the surface-level understanding of resiliency – ‘well, she copes very well most of the time’. If the utilization of a compulsive caregiving strategy fails to elicit much-needed caregiving, then children can utilize a compulsive self-reliant strategy. That is, they lose trust entirely in relationships being able to offer comfort and protection and seek emotional and practical independence.

Whilst these attributes are highly adaptive methods for survival, its tendency to be reduced to ‘resilience’ fails to acknowledge the complexities of trauma and risk. Although the SCR highlights perceived resiliency as a considerable barrier to understanding Sasha’s needs, it still fails to recognise the dynamic nature of resilience and instead treats it as a binary concept. It has transformed Sasha into a girl once considered highly resilient, mature, and articulate into the very opposite – a ‘pseudo maturity’ as if she has been trying to fool and manipulate professionals; once again shifting the blame but in a nuanced way.

Our propensity to treat resiliency as a binary concept negates the fact that resilience is multifaceted, and that people can be (and not be) resilient in a multitude of ways. Resilience is a wave to be ridden, a continuum that oscillates between moments of strength and moments of vulnerability. Sometimes the pendulum swings so quickly that strength and vulnerability become intertwined; to be vulnerable requires strength and courage, but sometimes our strength can become our greatest vulnerability.

In my experience, my inability to become vulnerable and express my needs and struggles was where my true vulnerability lied. I was so desperate to be loved, that the only way I considered this conceivable was to hide beneath my veil of resilience, no matter what the cost. I had learned growing up that the expression of my feelings or vulnerability would cause me to be rejected, and without awareness, I carried forward that notion into all areas of life. Those of us who have been parentified as children often find ourselves stuck in those same patterns throughout our time in care and beyond.

Whilst describing a child as ‘resilient’ can appear empowering, equally, it can perpetuate superhero rhetoric in which some children are perceived as having some inherent superhuman strength to withstand adversity. The messages that children may internalise from this are ones fraught with perfectionism and self-sustenance. They may learn that they only receive praise when they appear strong and able to cope (with pressures that no child should ever have to cope with, I hasten to add), and may keep things to themselves in order to appease those around them. This may reinforce the pre-existing coping strategy and prevent the underlying feelings of shame, inadequacy, and desperate need for intimacy, from being shown and acknowledged.

The concept of resilience therefore is used both as a way of glorifying a child’s trauma to serve as a palatable platter of inspiration for us to gorge on when we feel demotivated in our own lives but also as a way of palming off system-generated trauma as a consequence of a child’s inability to ‘bounceback’ from their adversities. The idea of resilience being a child’s responsibility to improve is pathologising – resilience does not occur within a vacuum of self, but is influenced and shaped by the systemic blockades individuals often find themselves trapped within. How can people ‘bounceback’ if they are trapped within the systems that are perpetuating harm and suffering? Instead of commending individuals for ‘bouncing back’ or criticising individuals for not having the stamina to jump, why are we not seriously considering why they are facing adversity in the first place? Just because individuals are resilient, doesn’t mean that they should be forced to endure the same pain and suffering over and over again. We commend the bouncing as if it doesn’t leave bruises and broken bones. At some point you are going to get tired of bouncing, just like how Sasha too grew exhausted; burdened by resilience.

Conclusion:

The truth is, the question should have never been about whether Sasha was resilient or not. No child should ever experience such traumas in the first place. No child should be burdened with pain so heavy that their only option is to take their own life. No matter how resilient you are, all it can take is a split-second to do something that you can never recover from. There is only so much suffering one human can take.

We need to look beyond narratives of personal resilience and begin to locate and disrupt the environments that are causing harm in the first place. We should be striving to create resilient systems, rather than expecting children we are supposed to be caring for to be responsible for their own.

By Lys Eden (14.08.20). You can check her out at twitter here.

If you have found this interesting/useful, you may wish to consider scrolling down to the bottom and signing up for free blogs to be sent directly to your inbox (no advertisements/requests/selling). I intend to write every fortnight about matters related to child protection, children and families, attachment and trauma. The next blog will be 10 lessons from 10 years on the frontline. Or you can read previous blogs here

BLOODY BRILLIANT BLOG.

Lys, you will go far with such clarity of thought and the ability to connect concepts to behaviour.

As a model/diagram lover, you created pictures with words wonderfully, which deepened my understanding.

You are absolutely right. We bandy words like resilience around without drilling down. Its complex. It can get dirty. Reminded me of Brene Brown and her shame and vulnerability research (Daring Greatly).

You Lys, are ‘Daring Greatly’; in the arena, striving valiantly; showing courage and vulnerability.

Many thanks to you both (Lys and Richard) for this magnificent blog

LikeLike

Amazing article

Thank you for sharing

LikeLike

So thought provoking, a brillant article.

LikeLike

Very thoughttful blog

LikeLike